During early December 2020, the Greek parliament approved a law for the export of antiquities, including entire museum collections, to foreign museums, institutions and, probably, foreign individuals.

Exporting-Selling Greek civilization treasures

The law would allow these precious Greek treasures to be away from Greece for a long time: the first proposal from the Greek Ministry of Culture was for a century, but reaction set in and modified the export for twenty-five years with possibility for another twenty-five years, all told half a century.

I don’t know the reasons for this insane decision. The Greek Ministry of Culture says the export of Greek treasures “promotes Greece’s cultural heritage worldwide.”

But no self-respecting government would do such a thing: export material evidence of great achievements in Greek history, and export those treasures for half a century, which means practically forever.

Thieves and looters of antiquities, including the British Museum that pretends it “owns” the Parthenon frieze Lord Elgin looted in early 1800s, would be vindicated for their criminal acts. They would cite this irresponsible and immoral law, saying the Greeks themselves are sending their patrimony for safe keeping to foreign places.

Foreign debt behind the sacrilege

There’s also the constant foreign pressure to repay the debt. This might explain the unexplainable, that the present Greek government has to find perpetual cash for its ruthless European-American colonial masters demanding a pound of flesh every day. The Greek museums – in the past non-pandemic days, were cash cows full of euros, which ended up in the European Union-International Monetary Fund (EU-IMF) debt machine.

So, it’s quite possible, that EU-IMF debt collectors cooked up the insulting law and the subservient Greek government did their bidding.

However, no matter what motivated the drafters of this bad law and those politicians who approved it, they better come to their senses and repeal their abhorrent legislation or the country of Greece will cease to be associated to ancient Greece. In fact, patriotic politicians should tell the EU-IMF tax collectors to get lost. Just like national defense, antiquities should be beyond outside interference.

My first visit to the Acropolis

Here’s why. I was born in the Greek island of Cephalonia in the Ionian Sea in Western Greece. The first time I visited the Parthenon was on the eve of my departure for America in 1961.

I was then a graduate of high school. My knowledge of ancient Greece was limited but enough to make my first contact with the Parthenon memorable. I kept looking at the wrecked temple and tried in vain to figure out who might have damaged such a gorgeous monument.

I knew then nothing about the repeated vandalisms of the sacred temple of goddess Athena by Christians, Moslems, and moderns like Turks, Venetians, Lord Elgin and Nazi Germans.

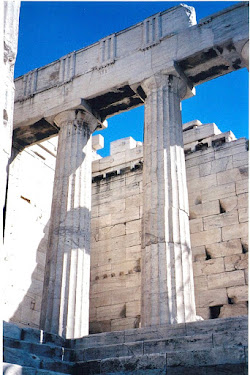

The marble columns seemed gigantic and mighty but expressed reason, harmony, and sophisticated architecture. Looking at them and their support of the roof and the entire building, they create the beautiful in reality and theory, a virtue the Greeks called the beautiful and the good, kalon k’ agathon.

I reconstructed in my mind the chryselephantine (gold and ivory) statue of Athena Parthenos (Virgin) by Phidias in the fifth century BCE. I even imagined the magnificent Panathenaic festival and athletic games honoring the divine protector of Athens, daughter of Zeus, Athena.

The Parthenon

Ploutarchos has something to say about the Parthenon. He lived from about 46 to 120 in our era. He was a Greek polymath, philosopher, prolific writer and priest of Apollo. He wrote almost six centuries after the Athenians built the Parthenon. He left a few clues of what and who made the Parthenon possible.

He reported that the materials used for the construction of the Parthenon included marble, bronze, ivory, gold, ebony and cypress-wood. The technicians who shaped these materials to form the Parthenon included carpenters, molders, bronze-smiths, stone-cutters, dyers, gold and ivory experts, painters, embroiderers and embossers. Add to these rope-makers, weavers, leather-workers, road-builders and miners. Then there were sailors and pilots who carried the marble by land and sea and trainers and drivers of yoked animals that did other indispensable work. All in all, some 200 craftsmen and 50 sculptors did the lion's share of work in the building of the Parthenon.

Ploutarchos says that the builders of the Parthenon tried to outdo each other in the beauty of their handiwork, which was inimitable in its perfection and grandeur.

In his Life of Pericles, Ploutarchos praised the Athenian leader for building the Parthenon. The works of Pericles, he said, were done in a short time and for all time. Each one of those works was so fresh, vigorous and beautiful that it was at once ancient; in fact, each work like the Parthenon looked as if it was untouched by time.

The French philosopher Ernest Renan, visited the Acropolis in 1865 and, like Ploutarchos, fell in love with the beauty and sacredness of the Parthenon. He saw the ideal crystallized in Pentelic marble. He praised Greece for its philosophy, science, art, and civilization. But when he saw the Acropolis, he admitted, he had the revelation of the divine.

Renan equated the beauty of the Parthenon with absolute honesty, reason, and the respect Greeks had towards their gods. He said the hours he spent on the Acropolis were hours of prayer to Pallas Athena (Prayer on the Acropolis).

I am not certain if, like Renan, I prayed to Athena, my favorable goddess. But my thoughts were pretty close to being a prayer. My first visit to the Acropolis and the Parthenon is still with me. I never cease learning from those Greeks who created so much science and civilization so fast, not merely for themselves but for all humans.

Don’t export Greek civilization treasures

The Greek government is wrong to start dispersing for fifty years (not different from selling) ancient Greek treasures. It has no right to destroy what survived endless dark ages and wars.

The Greeks in Greece and the rest of humanity have a right to demand that ancient treasures stay where they are: attracting year after year millions of tourists to Greece to come in touch with the beginnings of Western civilization and perhaps offer their prayers to Pallas Athena. I do that in every visit to the Acropolis.

Comments

Post a Comment